We’re advised to pay attention to interactions at work. It is believed that untapped performance potential lies in altering how people interact with each other, advocating investing in developing more productive workplace interactions.

Various research, and philosophies, articulate this sentiment in different ways, and from different angles. There are references to the importance of improving interactions in:

- Lean with its laser focus on cross-functional collaboration, value stream mapping to reduce handoffs, and dependencies, and Gemba-walks that attempt to optimize for solving creation problems where they exist.

- Beyond budgeting that targets decentralized decision making, empowered teams, and dynamic forecasts.

- Team Topologies with its teams types, and team interactions.

- The Agile Manifesto with it’s famous “Interactions, over processes and tools”

- Psychological Safety that aims at developing inclusive, open, communication and collaboration within and between teams.

- Conway’s Law noting that outcomes are the product of interactions that in turn are the function of structures.

The list goes on, and it does seem intuitive that how we interact is correlated with performance.

But, if observation of interactions is key, why aren’t there any comprehensive frameworks that guide us in observing interactions at work? How, exactly, should someone evaluate whether an interaction is constructive or not? And can such an assessment be universally consistent?

Nature to the rescue

This is where we can get help from nature, and particularly the field of ecology. Ecologists have studied relationships, and interactions between different species in nature over the past century and a half. And they[1] have developed a framework called “Interspecific Interactions” that can guide us in our work with enhancing organizational performance.

Five types of interactions

Interactions between species result in one of three potential outcomes for two involved entities, or species. The interaction can be beneficial, neutral, or harmful. For example, consider a bee and flowers. Their interaction is beneficial to both species exemplifying what is called a mutualistic interaction. Other instances of mutualistic relationships include the bond between mycorrhizal fungi and plants, as well as the symbiotic relationship between humans and our gut microbiota. Mutualistic interactions are desirable; we should encourage them.

Contrarily, interactions that are harmful to both parties fall under the category of “competition”. Picture lions and hyenas fighting for the same prey, a shared water source, or a particular territory (a deeper dive into competition follows later).

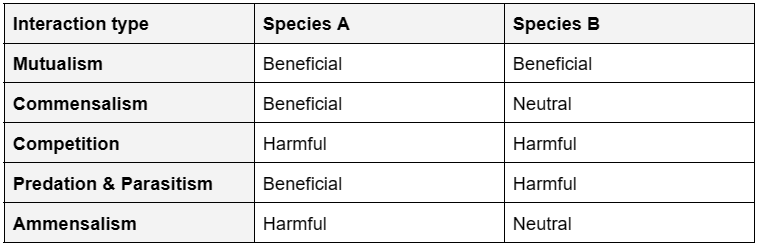

When graphed in a table, these dynamics translate into five distinct interaction types:

A table showing interspecific interactions [2]

Why interaction outcomes matters for performance at workplace

In nature, different species have complex relationships with each other. In the same way, our varied roles, and limited resources (whether cognitive cycles, money, or other essentials) at work can lead us to act as if we are distinct species, even though we technically are one–humans.

The framework Interspecific Interactions equips us with a shared language that we collaboratively can use at work to observe interactions, generate insights, and determine interventions that enhance workplace dynamics.

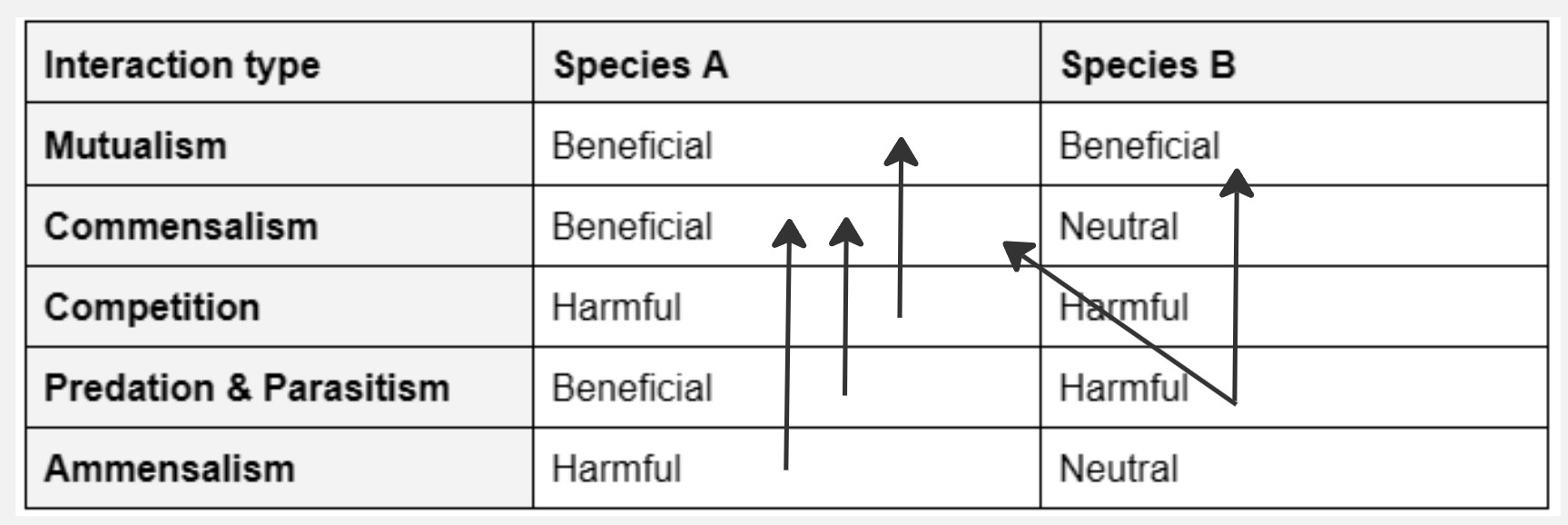

Reducing harmful interactions is a good use of time for any management team i.e. reducing competition, predation, and ammensalism at work.

A table showing the movement of interactions from harmful to beneficial

Predation at work

Predation is when one species consumes another – think lion and zebra (carnivore predation), or cow and grass (herbivory predation). Examples of predation at work are:

- Hostile takeovers. If you’ve seen the movie Who killed the electric car, that’s an example of a hostile takeover.

- Market predation. This is where one function at work launches a new solution that renders another department useless. This may be automation, self-service sales tools that render sales people unnecessary.

Parasitism at work

Parasitism occurs when one entity (for example customer support) relies on another (for example a development team) for its survival (reaching its goals) over time, without killing it’s host. Or at least not quickly.

In the workplace, this happens countlessly. Beyond the example above, think about how:

- sales is expected to reach targets that require new technical capabilities, while not having those abilities nor the influence over acquiring them so they have to resort to parasitism with development teams.

- A dominant team member assigning their work to a less assertive team member while not giving them room for growth, or recognition.

Competition at work

There’s a fundamental misunderstanding regarding competition as an interaction mode. You’ve probably heard the saying “a little competition never hurts anyone” but it lacks nuance.

Yes, it’s true that rivalry between companies, or teams in sports can elevate performance over time with one team emerging victorious. But internal rivalry for influence or resources within an organization erodes the organizational performance, both short and long term. So the effect of competition varies widely based on its context—within teams vs between teams in the same company vs between teams in different companies.

The internal competition some companies promote can be likened to a football team where offensive players count on defensive players’ support, but the defense acts contrary to this expectation. This dynamic is counterproductive, as neither group meets its objectives, and the only winner might be an external competitor (to the victor goes the spoils).

A more constructive approach to competition is collaborative ideation. Imagine two teams working together to develop varied solutions for a shared challenge. Afterward, they evaluate the best approach and collaboratively refine it. This enables relationships to form and in doing so also spurs innovation. If you’re thinking of this as competition, it’s better termed “collaborative innovation.”

But, many organizations misapply competition, like annual reviews where employees must prove their individual value, potentially at their colleagues’ expense. It’s misguided when firms expect team members to underscore their individual contributions to the collective, sidelining their peers in the process.

The concept that competition leads to “survival of the fittest” and overall species betterment oversimplifies evolutionary theory. While competition can spur adaptation, it’s essential to recognize:

- The importance of diversity: Resilient systems require varied inputs, and unchecked competition can diminish this diversity, like cancer.

- The role of cooperation: Evolution often hinges on mutualistic collaborations that benefit multiple species. This shares the energy cost for survival.

- The hidden costs: Competition is resource-intensive, consuming not only physical energy but also mental bandwidth. In a corporate setting, this might mean expending energy guarding against perceived threats from colleagues rather than focusing on shared goals.

- Adapting to competitive shifts doesn’t necessarily equip one to address the core challenges effectively.

So the thinking that “competition is good because it leads to higher performance” is in part an over-simplification, and in part just wrong–you’re more likely to wind up with lower performance at work.

Why do we have harmful interactions at work?

Three primary factors contribute to predation, and competition in the workplace:

- Misunderstanding performance drivers.

- Inability to evaluate interactions and their costs effectively.

- Scarcity due to the absence of a clear strategy and insufficient funding.

Whether it is a senior management team, or the leadership closer to the teams, when we jointly intervene to maximize beneficial interactions while minimizing harmful interactions, we can boost team performance and well-being. Not only does this reduce staff related costs such as recruitment, onboarding, knowledge transfer etc, but through more beneficial interactions you can also expect to see increased innovation.

How to use Interspecific Interactions to observe at work

To improve interactions, you could begin by examining your organizational chart:

- Map out departmental goals

- Identify which teams contribute to those objectives

- Assess when pursuing one goal inhibits another, indicative of a harmful interaction.

- Explore what incentives, skills, priorities, and structures need to change to shift from harmful to neutral to beneficial.

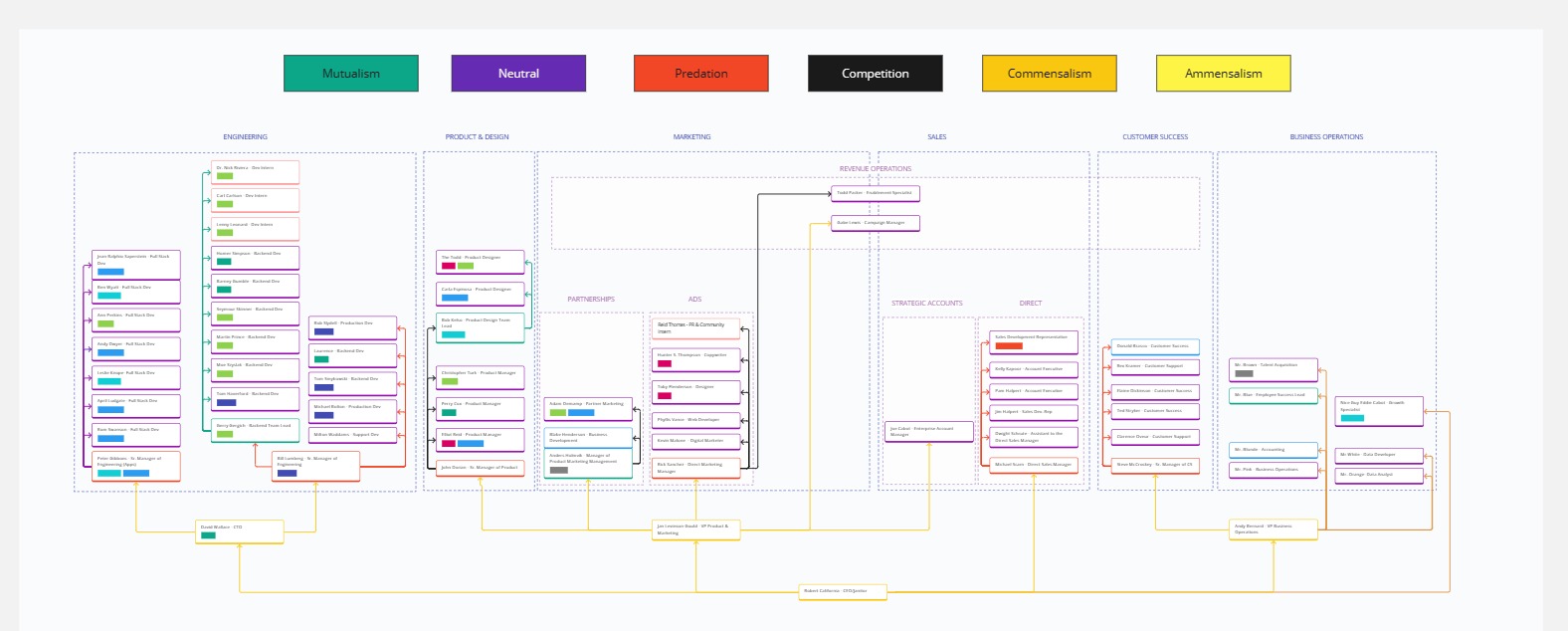

Fictitious example of an org chart indicating the outcome of the interaction through line color.

[1] Interspecific Interactions has been developed over a century with contributions from Charles Darwin, A.J. Lotka, Vito Volterra, Gause, E.Hutchinson, and R.MacArthur among many other ecologists and researchers.

[2] There’s also “neutral” consisting of bi-directional neutral outcomes.