The best way to kill a grassroots movement at your company is to assign an owner, sponsor, or steering group for it.

Below is a story about ACME, a fictitious software company, and how it responded to a grassroots movement. In the story, I discuss things to be aware of when new grassroots movements form both as a member of the movement and as upper management. I share pitfalls and summarize takeaways so that you can be more mindful of how to let the energy of grassroots movements flourish in your organization.

Grassroots movements have agency. What is agency?

Agency is power of action. It’s the ability of individuals to act freely and to make their own choices. When people share agency towards a common goal that challenges existing political and financial structures, a grassroots movement can form.

Agency makes management nervous

Companies often advocate self-leadership, empowerment, and agility, and genuinely want people to take action and make improvements. However, when ideas appear that put the current financial and power structures at risk, management gets nervous. Their response often includes interventions that reinforce compliance, stifling creative energy and overlooking the on-the-ground expertise of employees.

Balancing high levels of company-wide agency with compliance is difficult for management. And despite what they might claim, they often want agency within predefined boundaries, not full agency.

Let’s take a look at how this played out at ACME and how it may be playing out in your own workplace.

ACME: The Background

When ACME was founded, their business idea was to connect customers with factories to facilitate the sale of factory goods. As time passed, they expanded their business model to include selling logistics software and moved towards direct-to-consumer sales.

ACME’s teams and organization

ACME grew to 250 software development teams. Since they were founded, they’ve been organized in many different ways. From the inside it seems as if everytime a new executive comes in, she has ideas about how to reorganize everything in order to solve things “once and for all”. The company now finds itself in an oscillating pattern in which they centrally decide on how to reorganize the company each year.

There’s been complaints from developers about how constant reorganizations reduce performance and focus. That they destroy working relationships and cause a permanent sense of loss. But senior management doesn’t think this is as big of a problem as their staff does, so they’ve continued with yearly reorganizations citing that they increase clarity, alignment, and reduce conflict.

ACME’s most recent reorganization

In their most recent reorganization, ACME was divided into three new divisions, each with its own senior management team. ACME also moved the product managers out of the teams and out of the divisions into a sister company.

Not all teams would get to keep working with a product manager. In fact, ACME removed product managers altogether for teams not working directly with customers. “Why would you need a product manager if you’re serving internal users and stakeholders?” was the rationale. Senior management advocated that teams should take on product ownership as a shared responsibility as the “empowered teams” they are supposed to be.

In short, many teams lost access to product managers either partially or entirely.

Concerns were voiced

Serious concerns were voiced about this change. Losing product managers would make it more difficult for teams to know what to do, hurting alignment within and between teams. They explained how duplicated efforts would occur and divisions would become suppliers to the sister company rather than being driven by a shared north star.

But senior management and the sister company viewed the concerns as a sign that teams had not fully understood the change. They partially attributed the concerns to “stubborn developers” and “inexperienced managers” .

Concerns become reality

Fast forward one year: the situation for both internal-facing teams and customer-facing teams had now become unbearable.

The signs of entropy could be seen and felt throughout the entire organization: stressed middle managers trying to resolve tensions, conflict within teams, time spent solving the wrong problems, planning meetings dragging on, and a low ability to make the most of the opportunities that did arise.

What’s more, people were ultimately forced to neglect their role responsibilities to sort out the friction and inefficiencies caused by previous reorganizations. Talent management, career development, and recruitment suffered greatly. Senior developers were unable to solve important technical problems as they were busy trying to understand what was going on and implementing one-off quick fixes.

Dissatisfaction was high, eNPS was at a record low, staff was resigning, and it was difficult to hire new talent.

Dissatisfaction fuels agency

Slowly, among this dissatisfaction, a grassroots movement started to form. The movement started by people venting in social settings. People were frustrated and didn’t know what to do.

As they discussed their challenges, at first casually, they explored how they might address them. They found energy from being surrounded by other people with similar challenges and goals. Agency started to emerge.

Three areas of improvement

As time went on and the group became less casual and more like a structured community. They met regularly to explore the systemic patterns that had emerged. They soon identified three main areas that they believed needed changing.

The first was to (re)calibrate the expectations of middle managers. Middle managers had become so busy firefighting that they were disconnected from the bigger picture. Both in the sense of what their role was about, and what direction the company was heading in.

They needed support to heighten their perspective and start working more proactively. The first step was enabling them to better understand what they were spending their time on and what they were neglecting to do. The managers needed support in devising a plan for how to shift focus to the most critical activities, and they needed a community for knowledge sharing so that they could develop within their trade.

The second area was to create an assessment tool for the teams and divisions that explored work-environment, expectations, processes, product artifacts, and challenges. The grassroots movement believed that teams could make some improvements to their day-to-day environment by shifting their interactions and processes. The grassroots movement also noticed that many teams had stopped being teams when the product managers left. They wanted to identify if the team were even teams and the best setup going forward.

The third improvement was to bring back the product manager role. But not everywhere. It was only needed in teams that met certain criteria that they deemed most crucial.

In short, they noticed a need for leadership development, team coaching, and more focused roles and responsibilities by reintroducing product managers into teams. This meant a change in budgets but also that a number of policies ranging from roles and responsibilities, dealing with leadership gaps, and how to collaborate would need to change.

The grassroots movement worked on the first two points with a few teams, postponing a company-wide rollout attempt. With these teams, things improved.

At this point in time, the grassroots movement turned to the senior management team. They wanted their help and approval in rolling their initiatives out across the whole company. Reintroducing the product management role also meant reintroducing the budget for it and that meant having to get management’s buy-in.

Let’s explore how the three divisions responded to the grassroots movement, and how senior management dealt with the balance between compliance and agency.

Kill the movement fast

Division A was headed up by Lisa. On a Monday morning, Lisa opened her laptop and found an email from the group. They invited her to a meeting where they shared all their data, insights, and ideas. They showed her what they’d done so far with mentoring managers and coaching teams and the promising results they’d seen.

Lisa saw their work as a distraction from the teams delivering on their goals. She also thought that bringing back product managers would implicate her leadership.

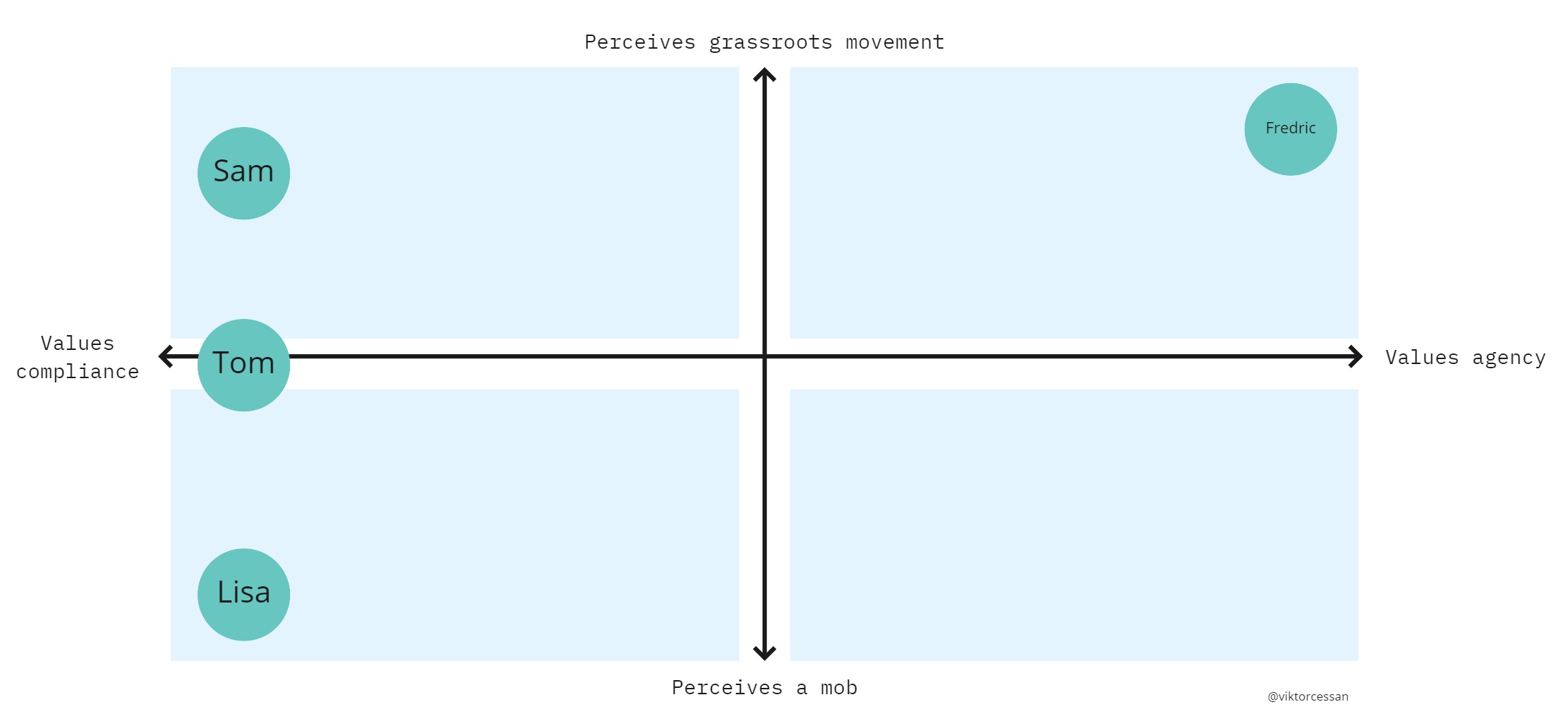

Lisa perceived the grassroots movement as the formation of a mob that was spiraling out of control, and she defined the problem as people not following organization-wide goals and policies.

No one else in the senior management team disagreed with Lisas analysis of the situation. They didn’t agree either. It didn’t really matter what they thought, Lisa had a plan.

Lisa gathered all the group members and let them know that the different teams’ goals were clear, that they didn’t need product managers, and failure to comply would be visible in the yearly performance reviews and possibly lead to termination.

Lisa used her power to make threats hoping it would lead to compliance. And, as you can imagine, it worked. The grassroots movement in the division came to a stop, and eventually most of the members of the movement left the company.

Within a six-month period, the grassroots members left or were replaced, and Lisa was happy because she no longer saw signs of any internal unrest.

Take over ownership of the movement

Division B was headed up by Sam. When Sam saw the email, he and the entire senior management team joined in on the meeting with the grassroots movement. They listened to their observations and their work and made an effort to understand. The management team agreed with a few of their points, but they thought there were some constraints that the movement ought to be aware of and boundaries they needed to comply with. “Some things are flexible, others are immutable,” they said.

Sam saw the group’s work as important to do so long as it didn’t interfere with the teams reaching their agreed-upon organization-wide goals. To show support and goodwill, the senior management team assigned an owner, Tom, of the grassroots movement.

Tom’s job was to empower the movement when they got stuck and to ensure they didn’t violate certain constraints (such as bringing back the PM role).

Tom met with members of the grassroots movement, and joined in on their group meetings to understand their perspective and their data. After a few of these meetings, Tom had reached a few insights that were different from those of the grassroots movement. He now perceived the group as well-intended but idealistic cynics. As Tom saw it, the problem was having incompetent staff that needed training.

Tom felt that the best way forward was to train middle managers and teams how to do product ownership. “Product ownership isn’t happening because teams and managers don’t know how to do it,” he said.

The grassroots movement disagreed with him and tried to engage him in dialog about the observations and needs. Tom wouldn’t hear it though. He soon took over the responsibility of sending out calendar invites to gain better control over the meeting, the participants, and agenda.

Slowly, members of the movement dropped off one by one and nothing changed. Sam was happy that nothing was stirred up now mid-reorganizations, and Tom was disappointed that the grassroots movement didn’t fix the problem he had identified.

Understand concerns and protect agency

Division C was headed up by Fredric. When Fredric received the email, he made sure to meet with the members himself first. He wanted to understand more. Fredric foremost saw it as his responsibility to grow company-wide agency, and he understood that inviting the entire senior management team could stifle the group’s agency.

Fredric saw the effort the grassroots movement had put in, and he recognized that the group had members from a variety of roles and teams that all were closer to the day-to-day environment of the teams than he himself was.

Fredric perceived the group as a grassroots movement with agency that needed nothing except helping in removing friction as they worked towards their goals. He defined the problem as an overconstrained environment and missing feedback loops.

Fredric asked the group what they needed from him in order to maintain agency. The group said they wanted to do an organization-wide assessment of all teams’ and middle managers’ situations. Fredric brought it up with senior management, an email was sent out, and it happened across the divisions.

The grassroots movement also said they wanted to bring back the product manager role in all teams. Fredric was a little on edge about this since he had some context he noticed the group lacked.

Fredric didn’t want to negatively influence their agency, but he also had context that he thought was relevant for the group to take part of. Instead of telling them what he thought they could or couldn’t do, he compared notes. They looked at budgets, labor laws, company goals, and customer data. In essence, he provided the group with data that enabled them to make more informed decisions.

With the added context about budget, goals, and labor laws, the group realized they couldn’t hire the 100 product managers they initially had perceived ACME would need. Not at once anyway. And especially not now while there were so many product managers at the sister company.

The grassroots movement decided to reallocate funds from hiring developers to instead hire 30 product managers for the teams that were struggling the most and that had no product manager at the sister company. They also made office space for ACME’s previous product managers. This way they could start sitting in the teams again, even if they didn’t change their official employment.

Fredric realized that these changes signaled that the past reorganization had real, significant shortcomings. It would be hard for upper management to admit–not just publicly but to themselves. But he also realized that two wrongs don’t make a right, and instead he worked to change the organizational constraints.

The group’s agency remained over time, and the situation improved in all divisions.

Grassroots movements are creative expressions of agency

When grassroots movements form, it’s a sign that an organization’s environment is misaligned with the values, goals, and needs of the people within them. A grassroots movement is the formation of agency in an effort to improve the current environment.

At ACME, only Fredric realized that this group wasn’t a gathering of disgruntled cynics, also known as a mob (a concept I’ll touch on a bit later), but a grassroots movement. He realized it was a sign of agency emerging and that this precious energy needed protection from compliance-inducing interventions.

Lisa perceived the group as a mob that needed to be stopped as soon as possible before they stirred up problems. Since she saw the group this way, her main goal was to enforce compliance through threats.

Sam also saw it as a grassroots movement just like Fredric, but Sam was sensitive towards the organizational constraints and also wanted to create compliance like Lisa. Sam was somewhere in between Tom and Lisa in his perception, but because he lacked the tools to collaborate with the group members he fell back on what was easiest: forcing compliance.

In the case of Lisa, she went in hard and shut down the movement. But compliance can also come in other forms such as by ignoring or deflecting requests, by actively sabotaging a movement’s efforts, or by changing the intention/goal of the movement–like Tom did.

How senior management perceives grassroot movements and how they perceive their role and goals determines the future of the grassroots movement and thereby the outcomes it can generate.

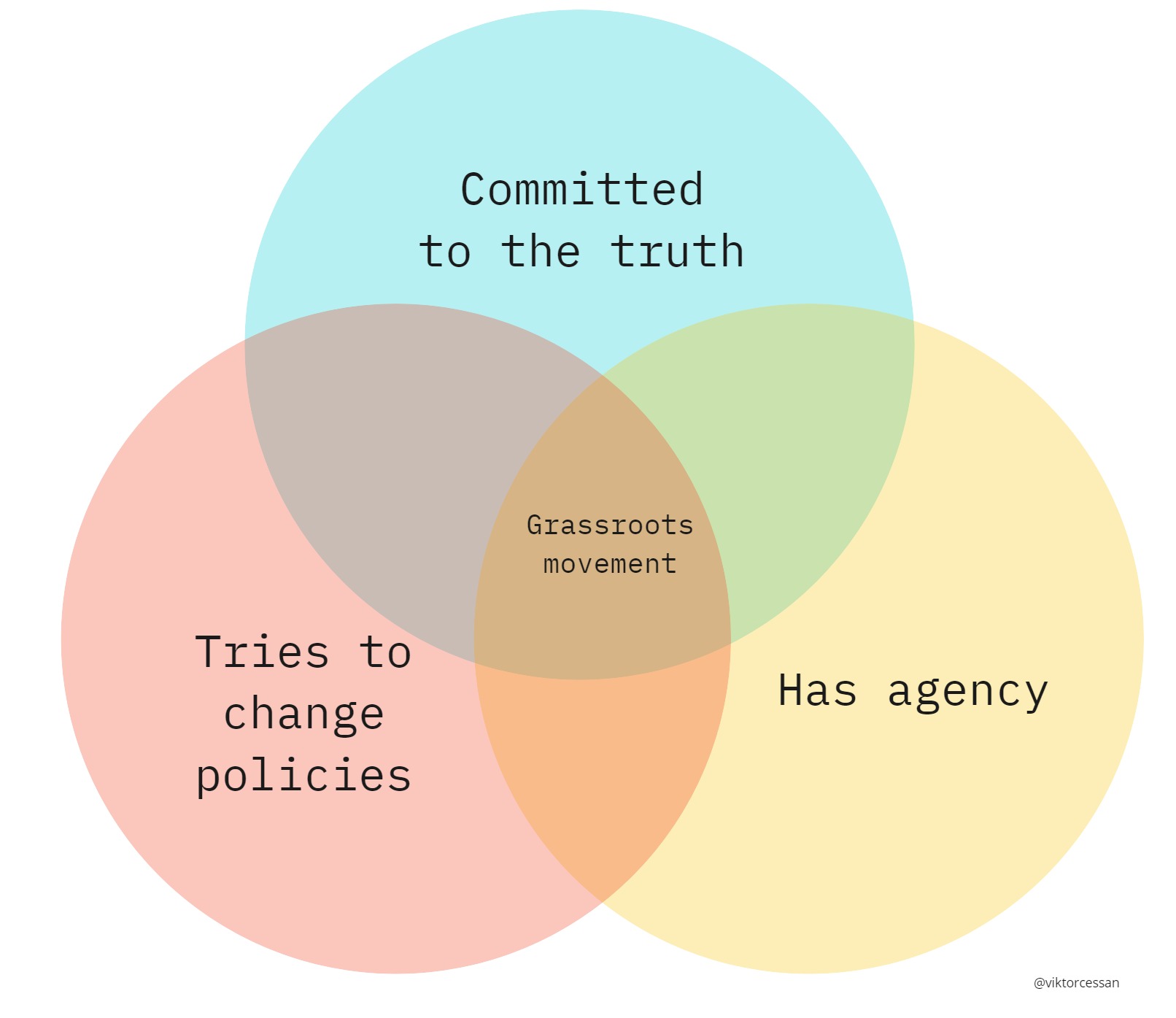

Mobs vs grassroots movements

If you’re wondering how to tell the difference between a mob and a grassroots movement, you’re not alone. A grassroots movement is very different from a mob which has the goal of causing conflict, violence, and stirring up problems for other people. So it’s understandable that management can get the two confused. To be fair, sometimes even mobs perceive themselves as grassroots movements when they are not. The differences are subtle but significant.

First, consider if the group has sufficient context and is anchored in reality. Multiple aspects of reality, not just one. Is the group changing their perception and mental model as they discover things? Are they modeling and remodeling? If so, that’s great, there’s a commitment to truth. If not, it’s leaning towards the group being a mob.

Second, grassroot movements are oriented around policies, so there’s a system orientation. Grassroot movements at work are not about one specific technology that someone wants replaced that happens to coincide with their favorite programming language, or collaboration tool, etc. Microsoft teams vs Slack is not a grassroots movement.

Third, grassroot movements have agency.

Considerations for agile coaches

Over the years working with other coaches, I’ve noticed a tendency for coaches to perceive teams as innocent and management as malevolent. A tendency to have a view that any bottom-up movement is a grassroots movement and that all things done bottom-up are always for the better of the company. That’s not always the case.

I also see coaches trying to protect grassroot movements from context thinking that context means exterior influence or manipulation. But without proper context, you have a mob.

Take the example of Fredric who had context about budgets, company direction, and labor laws that the grassroots movement lacked. If the movement wouldn’t have received this context information, their attempts would have failed. Context is crucial. If you, as a coach, are aware of people with relevant context, you can help increase the movement’s odds of success by connecting them with more context.

Considerations for grassroot movements

Grassroot movements are by nature decentralized. As soon as you expose a decentralized movement to a central governance team, tensions will naturally arise due to differing goals and perspectives, and different system structures.

As a grassroots member, this is a difficult balance to strike. Because if you ask for support and approval, you risk your movement coming to an end. And if you don’t ask, you’ll soon find yourself running into ceilings and bureaucracy, and the movement will come to an end.

Considerations for management teams

If you’re really serious about wanting high levels of agency in your organization, and you notice or are invited to a grassroots movement as a sponsor, first take time to understand. Avoid assigning any owner, or sponsor, and make sure the movement has your context, but don’t try to overwrite their reality with yours. Instead, offer context.

History plays a part as well. Go through the history with the members: What was it that got you here? What is the vector you’re on right now? How does this movement hope to change it?

Finally, explore what the movement needs in order to maintain their agency. It could be as simple as asking the movement to let you know when their agency decreases. Or to ask them what gave them agency in the first place and work to protect that.

The book “The Spider and the Starfish” covers centralized and decentralized organizations and offers additional insights.

Striking balance

Striking a balance between compliance and agency is difficult. While often well intended, interventions from upper management often result in stifled agency. Possibly, if you’re upper management, after having read this post you’ll think twice when you notice agency and listen more. And if you’re in a grassroots movement, perhaps you’ll think twice before exposing your movement to approval from the authority that it challenges.

P.s. I’m looking for examples of grassroot movements that have succeeded and failed. If you have a story to share, send me an email–I’d love to take part of your stories.

One Comment

Steven

Really great post. I can definitely recognize some of the characters you mention.